BANGALORE, India — The ruling Bharatiya Janata Party is famously obsessed with the cow, which is venerated in Hindu cosmology. Most Indian states have now banned cow slaughter. The government of Punjab wants to tax alcohol to pay for shelters for stray cattle. Last year, after a Muslim man in Uttar Pradesh was lynched by a mob for eating beef, a cabinet minister from the B.J.P. demanded to know who else was “involved in the crime” — meaning the beef eating, not the man’s killing.

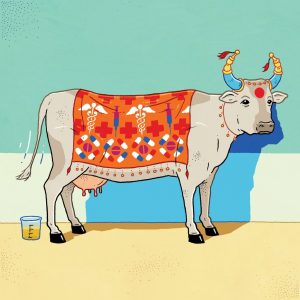

It should probably come as no surprise, then, that the B.J.P. is also touting the medicinal virtues of consuming cow urine. The therapy is mentioned in the Ayurveda, an ancient healing system described in Hinduism’s foundational texts. In the early 2000s, when the B.J.P. led the governing coalition of the day, the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, a state-funded network of research laboratories, started promoting cow-urine technology as a treatment for diabetes, infections, cancer and even DNA damage.

Today, the Indian government holds more than a dozen patents related to cow urine and has filed applications for them in nearly 150 countries. Many nations, including the United States, France and South Korea, have recognized these, but not India, which has much stricter standards for patents. For now.

The B.J.P. government released India’s first National Intellectual Property Rights Policy last month, and it is dangerously misguided. Although the paper reaffirms the basic tenets of India’s admirably farsighted patent laws, it also calls for protecting traditional remedies like cow urine. Taken to its logical conclusion, this policy could open the door to many more exceptions, playing into the hands of patent-happy international pharmaceutical companies.

Big Pharma justifies aggressive patenting by claiming that profit-making drives invention by giving labs and companies an incentive to invest in research. Indian law takes the opposite view: Higher standards for legal protection leave more room for innovation. Unlike many other countries, India does not allow patents for natural substances, traditional remedies, frivolous inventions or marginal innovations.

This is a good thing — a great thing, in fact. Having fewer patents means more competition for more generic drugs, which means more affordable medicine for more people. Imatinib, a drug used to treat a form of leukemia, is available in India at about one-tenth the price it costs in much of the world. In 2000, when the only anti-retroviral drugs for HIV/AIDS available were produced by Western companies, the annual cost of treatment was about $10,000. The price has dropped to about $350, at least in the developing world, thanks to generic equivalents that were developed in India.

Naturally, all this drives Big Pharma mad. Its business model relies largely on patenting small tweaks to existing technologies, which multiplies financial returns with only minimal investment in research. A recent Plos One study found that about 36 percent of all new drugs approved in the United States between 1988 and 2005 were protected solely by secondary, or trivial, patents.

This, being precisely what Indian law prohibits, has made India a fixture of the “Priority Watch List” of the U.S. Trade Representative’s Special 301 Report, a kind of most-wanted roster of the world’s intellectual-property deviants. Ahead of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s visit to the United States last week, 17 U.S. industry associations, including the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America, wrote to President Obama to complain about India’s business environment, in particular its patent laws.

Back in 1970, India withdrew drug patents in order to support its generic-drugs industry. They were reintroduced, with caveats, in 2005 when the country’s entire intellectual property regime was updated to comply with World Trade Organization rules. Acting on the advice of public-health activists, a group of Communist parties that formed an indispensable minority of the governing coalition forced the Congress Party to go along with the innovation-friendly restrictions that remain today.

Last month, when the B.J.P. announced its new intellectual property policy, it in effect repeated India’s longstanding response to its critics: Tough luck; our patent laws comply with W.T.O. standards, and that’s that. Or, as Mr. Modi himself put it when he addressed the U.S. Congress last week: “India’s ancient heritage of yoga has over 30 million practitioners in the U.S. It is estimated that more Americans bend for yoga than to throw a curve ball. And no, Mr. Speaker, we have not yet claimed intellectual property rights on yoga.”

But there’s yoga and then there’s cow urine. Even as the Modi government’s new policy paper reiterates the need to limit patents in the name of public health, it repeatedly argues for plucking “traditional knowledge” out of a multimillennial cultural commons and patenting it.

With this move the B.J.P. is picking up unfinished business from its previous excursion in power, when it led the National Democratic Alliance government between 1998 and 2004. That was the time when the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research and the Center for Research in Cow Science, an outgrowth of Hindu nationalist groups, first tried to patent cow-urine technology in India.

According to the Hindustan Times, over the last decade the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research has spent around $50 million on patent applications, including for using cow urine in health tonics, energy drinks and chocolate. The health ministry’s special department for traditional knowledge — known as the AYUSH department, for Ayurveda, Yoga & Naturopathy, Unani, Siddha and Homoeopathy — was elevated to a full ministry after the B.J.P. won the general election in 2014.

Patenting cow urine is a natural extension of the Hindu right’s obsession with the cow. It makes ideological sense for a nationalist party that rides on a wounded Hindu psyche to claim that Indian science was well ahead of Western science. But this is bad history. A large part of what India claims as its indigenous heritage isn’t exclusively ours: Unani medicine comes from Persia; the origins of homeopathy are German.

The B.J.P.’s nativist, Hindu-pride approach to patents is also bad economics. It unwittingly serves the interests of Big Pharma, and in time this will undercut India’s own pharmaceutical industry, which generates some $15 billion in annual revenues even while producing affordable drugs that benefit the public.

India’s patent laws, currently under consideration as a model in South Africa and Brazil, are a world-class innovation; our cow-urine technology, which has yet to garner much interest abroad, is not. To patent cow urine isn’t just silly. It also endangers a remarkably innovative patent system that has served India’s people and many others around the world so well.

This article was originally published in The New York Times on June 16th, 2016.